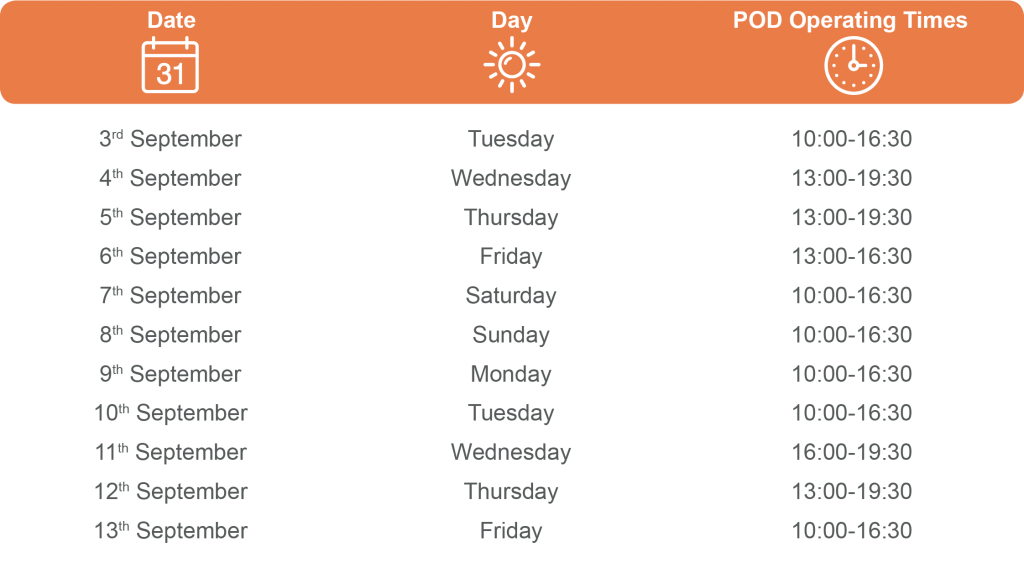

Capri pods are currently transporting members of the public around the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park with visitors able to test out an innovative mobility service. The trial will finish on Friday 13th September.

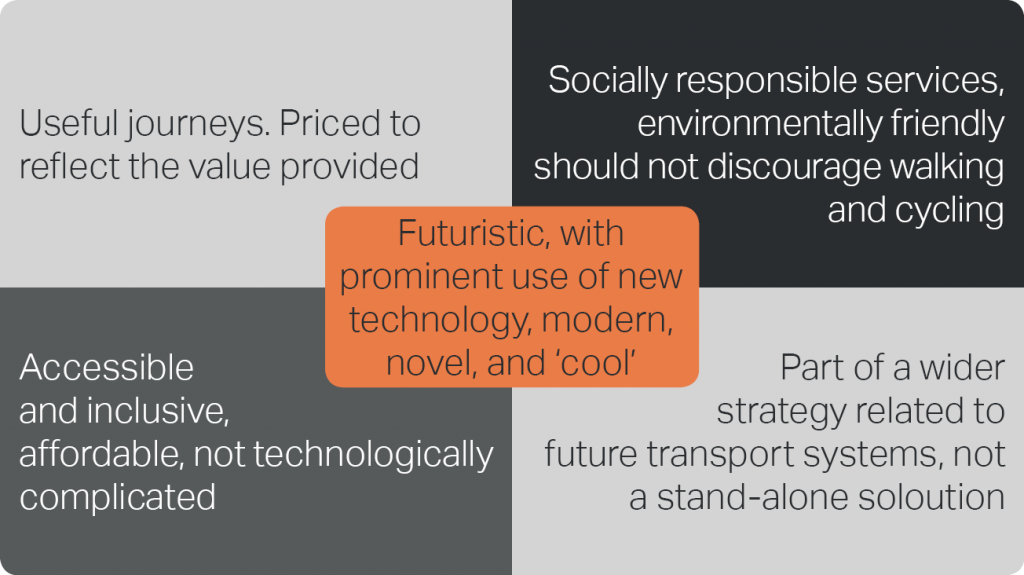

Visitors can book a ride using an app through information marshals located at different stops along the pods’ route. When booking a journey, participants can choose which stop to be picked up and dropped off from, with the system giving destination instructions to the self-driving vehicles. Simulating an on-demand service, the trial will help support the wider rollout of driverless shuttles in the future.

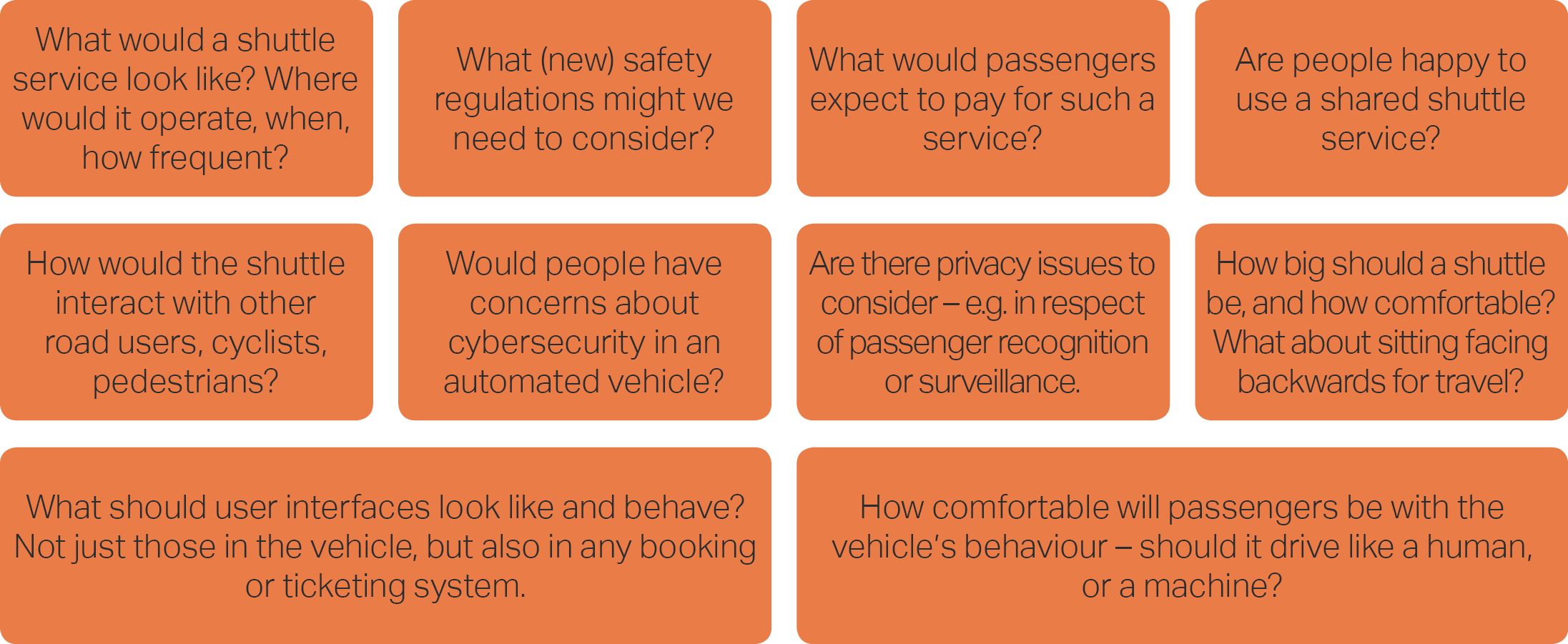

As well as testing and assessing the technology an important element of this trial will be to understand people’s behaviours and attitudes towards driverless pods. Capri partners University of the West of England and Loughborough University will be observing how people behave when confronted by the pods, as well as surveying passengers who take a ride on them.

What’s happening and when?

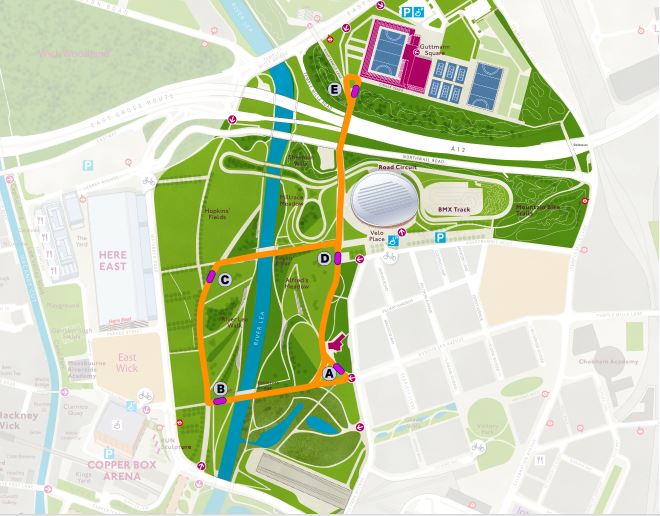

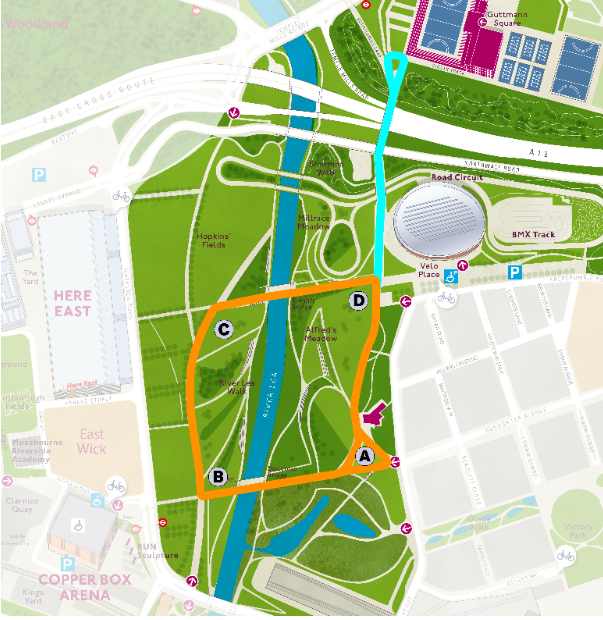

This trial at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is the first public appearance for the Capri pods, which will pick up and drop off passengers at different points on a circular route, passing the Lee Valley VeloPark, Copper Box Arena, Here East and Timber Lodge Café. See map below.

Local schools will also be participating, with two engagement days taking place to promote Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) activities.

https://www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/capri-pods-tested-by-manorfield-pupils-1-6259717

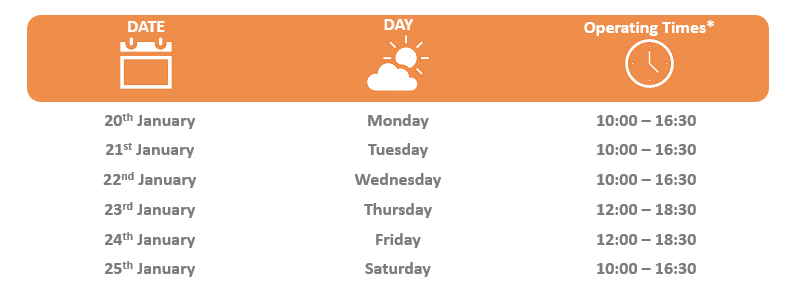

The current programme is provided below (please note this is subject to change on a daily basis).

Following this trial, the Capri pods will be at The Mall in South Gloucestershire in early 2020, returning to the Park next year with a final trial that will extend their route and further test the on-demand technology.

Following this trial, the Capri pods will be at The Mall in South Gloucestershire in early 2020, returning to the Park next year with a final trial that will extend their route and further test the on-demand technology.

Consideration of vulnerable road users

The Capri pods are operating within the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park using the wide walkways along a designated route. The pods are wheelchair accessible and information marshals are on hand to support any queries or requests members of the public may have. Whilst moving within the park the pods make an audible sound to make people aware of their presence. Safety mashals follow the pods and advise park users how best to interact around the vehicles. In the future Capri pods have the potential to provide significant benefits to vulnerable road users, extending accessibility and providing an enhanced, personalised and responsive service for all passengers.

Approach to safety

Prior to this public trial we have undertaken rigorous safety testing of the Capri pods, performing a wide range of tests in a closed site. The tests have been tailored to match similar conditions we expect to encounter at the park, in particular the interaction with scooters, bicycles, sharp turns, and low lying objects. The tests (run by Loughborough University) were passed by the pod, and using the results we have prepared a rigorous safety case for the operation of the pods at the park. The safety case has bene approved by key stakeholders including the London Legacy Development Corporation (who operate the park) and the insurers for the trial. The safety case includes detailed documentation of the design and testing of the pods, and key risks and mitigation strategies. A Safety Steward is always be in the pod whilst it is running. The Safety Steward monitors the progress of the pod and is able to stop the pod and disengage the autonomous control system at any time using a mechnical device. The use of a Safety Steward is standard practice for trialing in the UK. Given the unique nature of the trial we have decided to use safety marshals who are monitoring the pod and park behaviour at all times, and pre-empting any potential issues.

Following this trial we will review the role of the Safety Steward and Safety Marshals and consider whether they are necessary for subsequent trials. Afterall, the pods eventually need to run fully autonomously!

What data is being collected?

During the trial a wealth of data is being collected to support the operation of the trial and inform our future research and development. This includes three key areas:

- Data from the pods: We are logging data from the pods in real time including position, speed, mode, and sensor data. The information is kept after the trial and will be “replayed” to help analyse and understand performance. This will help with future development. We will log the requests made by participants via a tablet held by an Information Marshal. This information is not traceable back to the individuals.

- Participant questionnaires: We are asking trial participants to undertake a survey after their ride so we can understand what users think about the service. The survey can be completed online or via a hard copy with one of our Information Marshals. The results will help us to understand user attitudes and requirements, informing wider service design and deployment requirements. Questionnaire responses are anonymous.

- Behaviour of other park users: Video, observational and questionnaire data is being collected to capture how other park users navigate around the pods. This will help us understand wider behaviours including how people give way to pods, whether people try and make eye contact with a non-existent driver, and how closely people appear to be comfortable passing in front or alongside it. This helps inform the wider service design. Data derived from the videos is anonymised; once analysed the video data will be discarded. This helps inform future safety testing requirements and the wider service design. Behavioural data outputs derived from the videos is anonymised and no attempt will be made to identify individuals; raw video data will only be used internally within the consortium and will not be made public. During data collection signs will be put up to notify members of the public that filming is taking place, and filming will be stopped should any members of the public request not to be captured.